Our thoughts shape our lives, impacting our inner atmosphere, colouring our beliefs, and influencing our behaviour. Much of the time they run amok, pulling us hither and thither, landing us in places we’d rather not be. But if we’re mindful of our thinking, we can make wise choices about how we’re relating to ourselves and the world around us. We gain the freedom to live our lives from a place of clarity and wisdom.

There’s an old proverb that states “The mind is a wonderful servant but a terrible master.” And it’s true our capacity to think affords us many useful advantages. Indeed, the many marvels of human ingenuity all began as thoughts: the Great Pyramids of Giza, the printing press, Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, the theory of relativity, and Van Gogh’s Starry Night all first emerged as formations in the mind.

However, when thinking goes unchecked, our experience is prone to becoming one of turmoil and dissatisfaction. But by being mindful of our thoughts we can harness the power of the mind to achieve beneficial and beautiful outcomes. The Buddha put it this way:

All that we are is the result of what we have thought: it is founded on our thoughts, it is made up of our thoughts. If a man speaks or acts with an impure thought, pain follows him, as the wheel follows the foot of the ox that draws the carriage.

All that we are is the result of what we have thought: it is founded on our thoughts, it is made up of our thoughts. If a man speaks or acts with a pure thought, happiness follows him, like a shadow that never leaves him.

— From the Dhammapada (trans. Max Müller)

Noticing thoughts

When developing our mindfulness muscle, we generally begin with the breath and the body. This is because physical sensations serve as a readily accessible anchor that can ground us in the present moment, providing a tangible point of focus for our awareness. By directing our attention to the somatic experience of breathing, and by tuning into the various sensations present in the body, we cultivate the foundational skills necessary for mindfulness.

However, as we deepen our practice, it becomes increasingly important to expand our awareness to include mental formations. Thus, we start to cultivate the capacity to perceive our thoughts.

Noticing the phenomenon of thinking involves developing our faculty for observational awareness and directing it toward our inner landscape. This is a bit like learning how to watch leaves drift along a river without getting wet. Gradually, we expand our ability to witness thoughts appear and disappear in the stream of consciousness while managing not to get swept away by its currents.

As is the case with developing mindfulness as a whole, we grow our capacity to be mindful of thoughts via both formal and informal practice. In other words, we develop our ability to notice the mind is thinking by making this a focus when we meditate and also by paying attention during our day-to-day activities.

In both formal and informal practice, the key is to approach the experience with an open mind and gentle curiosity. Rather than striving to control or suppress our thoughts, we simply notice them as they arise, allowing them to unfold naturally. In doing so, we develop a sense of ease and spaciousness within our minds, enabling us to navigate our lives with greater clarity and freedom.

Always thinking

The mind continuously produces thoughts in much the same way the body produces hormones. It’s a natural, automatic process, occurring without any conscious effort or intention. And just as the body manufactures biochemical signals to maintain homeostasis, the mind generates thoughts to process information, make sense of the world, and respond to internal and external stimuli.

When we first learn to meditate, typically by maintaining focus on a meditation object like the breath, sounds, or a mantra, it can be something of a shock to encounter this tendency of the mind to always be thinking. We come to recognize, perhaps for the first time, that thoughts are constantly emerging and falling away and we have little sway over them. Indeed, thinking is a persistent and involuntary phenomenon.

If we believe the goal of meditation is to stop the mind from thinking, then encountering this cascade of perpetual thoughts can be disconcerting or even upsetting. We might come to mistakenly believe that the busyness of our mind makes us a bad meditator. But this is a fallacy.

What’s important to understand is that almost everyone has a busy mind, and this isn’t a predicament unique to any individual. And so the beginning meditator who becomes aware of this quality of the mind as always thinking is in fact succeeding in becoming more mindful. Each time the meditator recognizes they’ve been lost in thought, each time they emerge from the stream of thinking and realize they were immersed in thinking, is a moment of waking up. And the appropriate response to this moment of awakening should be one of congratulations, not self-recrimination.

The nature of thoughts

Though everyone has thoughts, we all experience the phenomenon of thinking somewhat differently. For some people, thoughts manifest as audio soundbites, consisting of words and phrases or an internal monologue. Others may experience them as fleeting images, vivid mental snapshots that arise and dissipate in the blink of an eye. Still others may perceive them somatically, and some may sense them as emotional responses.

The content of our thinking can also vary widely, ranging from mundane observations to profound insights, from worries and judgments to vivid fantasies and cool calculations. Our thoughts can reflect our past experiences and future aspirations, as well as our innermost desires and fears. They also tend to be influenced by external factors such as our environment, social interactions, and cultural conditioning.

Despite these personal differences in forming and experiencing thoughts, there are a number of universal attributes worth noting. One of the most significant of these is that thoughts, regardless of their form or content, are inherently transient. They emerge out of the ocean of the unconscious mind like waves that swell and crest and then crash on the shore of our awareness—there one moment and gone the next. They arise spontaneously, linger for a moment, and then fade away, only to be replaced by yet another thought. They come and go, an ephemeral, impermanent, and passing phenomenon.

Another quality of thoughts that’s important to understand is they influence our emotions and thus our behaviours. Our thinking can generate the felt experience in our body of fear, sadness, joy, anger, aversion, desire, and more. While some thoughts uplift our mood and motivate us to pursue our goals, other thoughts can lead us to experience anxiety, stress, and self-doubt. Indeed, our thoughts have this powerful way of impacting our lived experience, shaping our perceptions of ourselves and the world around us.

It should also be pointed out that the relationship between thoughts and emotions is reciprocal, forming a two-way feedback loop that influences our mental and emotional landscaping. This dynamic interplay between thoughts and emotions underscores the interconnectedness of our inner experiences and highlights the importance of cultivating not just our capacity to be mindful of our thinking but also to foster an awareness of our emotions.

Finally, it’s important to understand our thoughts, especially those that emerge repeatedly, impact our views about ourselves, others, and the world around us. Recurring thoughts tend to become ingrained as core beliefs, influencing how we perceive ourselves and our capabilities, as well as our concepts about others, the spaces we inhabit and the outcomes of events.

If we become mindful of the patterns of thinking contributing to our beliefs, we can challenge and reframe them. A process of cognitive restructuring can help us, for example, to break free from the constraints of negative self-talk and cultivate a mindset of self-compassion and resilience.

In essence, understanding the nature of thoughts involves recognizing their transient and influential qualities. By cultivating mindfulness of thinking, we can foster more advantageous modes of being.

Real, but not true

Thoughts are not facts. This statement may seem obvious, but all-too often, we mistake our thoughts for what’s real. In truth, thoughts are only a representation of reality, no closer to the real thing than a photo of a maple tree would be to a living maple—to the tree’s dynamic and shifting experience of budding in spring and dropping leaves in fall and its deep, winding roots absorbing nutrients from the earth and its raised branches reaching toward sunlight. The image is merely a two-dimensional depiction while the tree is a living, breathing being inhabiting its own experience.

Tsoknyi Rinpoche, a Tibetan Buddhist teacher and master of the Dzogchen tradition, uses the phrase “real, but not true” to describe the nature of our thoughts. In his teachings about this, he points us toward the importance of recognizing the illusory nature of thoughts. And indeed many of our ideas and conclusions are distorted.

Though thoughts certainly have an impact on our emotions and behaviour, they’re not accurate reflections of reality. Rather than being objective truths, they’re subjective interpretations. A map of the thing—sometimes useful, sometimes misleading—but not the thing itself.

To better understand how our thoughts can lead us astray, it’s helpful to recognize the influence of cognitive biases on how and what we perceive. These are hardwired fallacies in thinking encoded on the human brain that impact how we discern and interpret information. Though advantageous from an evolutionary perspective, they often lead to errors in reasoning.

One common cognitive bias to be aware of is what’s known as confirmation bias. This tendency of the mind causes us to perceive, interpret, favour, and recall information in a way that affirms pre-existing beliefs. It leads us to only notice information that aligns with our current views while disregarding or downplaying evidence that contradicts them. Confirmation bias perpetuates narrow-mindedness and hinders our ability to consider alternative perspectives or objectively evaluate new information.

For example, let’s say a person believes all cats are unfriendly. Every time they encounter a cat that hides, hisses, scratches, or simply slips away they nod to themself, thinking, “See, I knew it.” But when they meet a friendly cat, they simply dismiss it as an exception. This person fails to question their belief, even when new evidence presents itself.

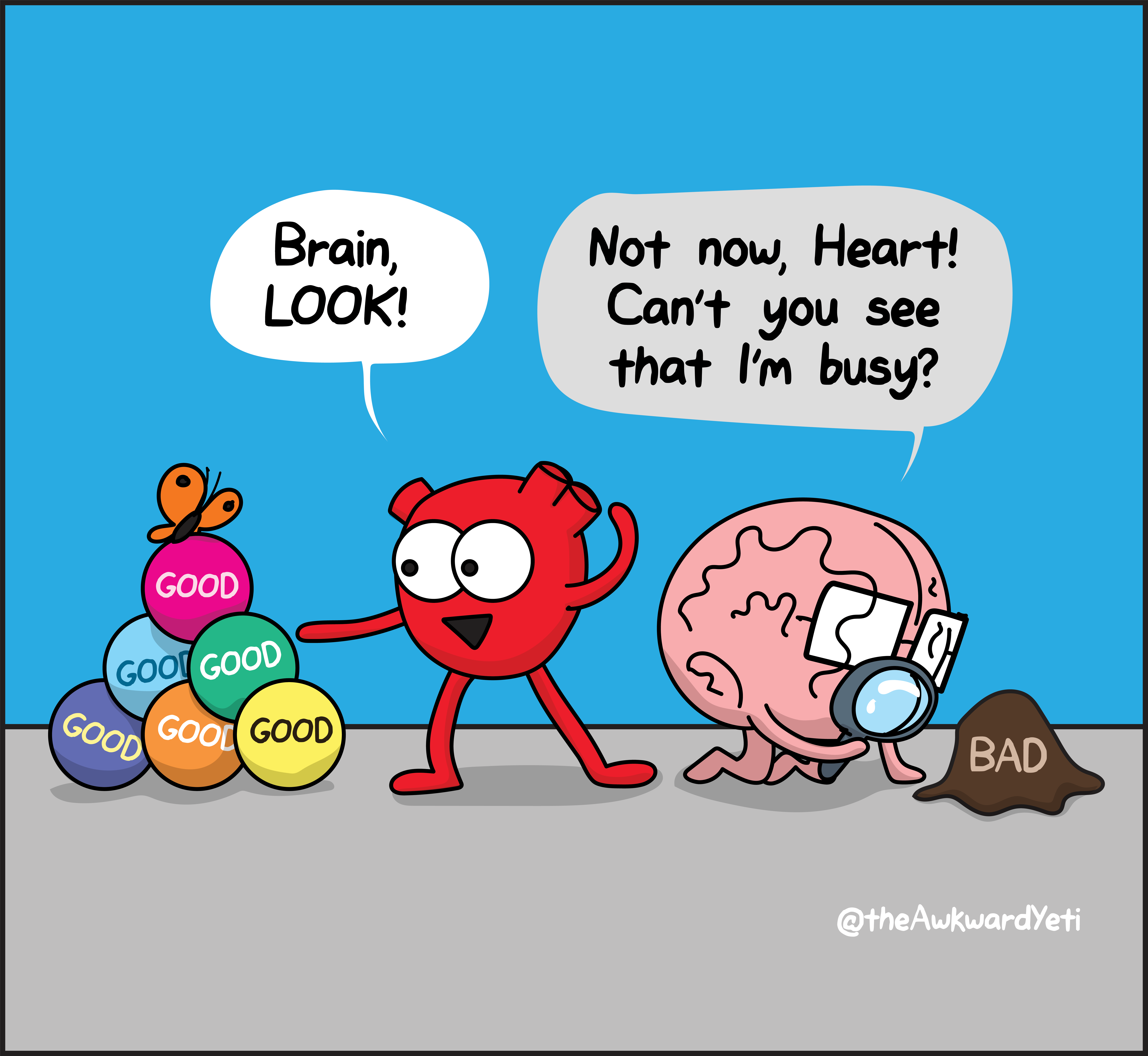

Another cognitive bias that has a powerful influence on our perceptions and beliefs is our negativity bias. This inclination of the mind predisposes us to pay more attention to difficult and challenging experiences than easy or uplifting ones. Our negativity bias evolved as a survival mechanism to help us detect and respond to potential threats in our environment. While useful to our ancient ancestors, in contemporary times, this bias is more harmful than helpful. All too often it contributes to heightened levels of anxiety, stress, and pessimism.

So for example, let’s say someone receives a performance review at work. Their supervisor gives them mostly positive feedback, praising their hard work and dedication. However, the review also notes one area where they could improve. Despite the abundance of positive feedback, they find themselves fixating on the one critique and dwelling on it long after the review is over. This person fails to give any weight or credence to the praise they received, and instead focuses only on the unfavourable remarks.

When it comes to developing mindfulness of thoughts, becoming aware of our cognitive biases and understanding how they can distort our thinking is very powerful. With this awareness we can begin to mitigate their influence and make more beneficial decisions about our lives. We can ask ourselves, “What am I believing?” And then, “Is it true?”

In this way we can become aware of our thoughts as constructs and learn how to wisely relate to them. Practising mindfulness of thinking allows us to grow our capacity to question the validity of our thoughts and consider alternative perspectives.

Meditation practice guidelines

If we have even a modicum of experience meditating, we’ve almost certainly already encountered the thinking mind. But how can we work wisely with these thoughts?

To begin with, we apply the general principles of cultivating mindfulness to our practice. We choose a meditation object like the breath or sounds, and then use it as an anchor to return to the present moment every time we drift away from the here and now.

We observe the experience of thinking with friendly interest. We also aim to witness our thoughts without judging, analyzing or getting swept up in them. And, to the best of our ability, we remain embodied as we practise.

Here are some additional methods we can use when we meditate to cultivate mindfulness of thoughts:

1. Note when we notice thinking

Every thought has a beginning, middle, and end. In the moment of becoming aware a thought is occurring, we can reflect on what stage of the thought’s existence we noticed it. Did we become aware of the thought as it emerged? Did we notice the thought in the middle of thinking it? Or maybe we observed the thought as it was falling away? Alternatively, did we only notice the thought after it had passed?

By tuning in to the various stages of a thought’s existence, we come to recognize the transient and ephemeral nature of our thoughts. We also grow our capacity to be simultaneously interested and detached from them while becoming better acquainted with our individual patterns of thinking.

2. Label thinking as thinking

Another technique we can work with is labelling. When we notice we’re thinking, we can silently make the mental note “thinking.”

For example, if we notice we’re having the thought what should I make for dinner, instead of mentally reviewing our repertoire of recipes or investigating the contents of our cupboards, we simply note “thinking” and return our attention to our primary meditation object (ie. the breath, sounds, etc.).

This practice can help us disentangle ourselves from the narrative of our thoughts so we can stand back and better observe them from a distance. It allows us to create space between the one who is thinking and the one who is observing the thinking.

3. Define genres of thinking

A similar technique to the one above involves labelling the category of thought. With this method, when we become aware we’re thinking, we silently note the genre of thought.

Some common categories of thought include remembering, rehearsing, judging, comparing, planning, fantasizing, and so on.

Before we sit down to meditate, it can be a useful exercise to write out a list of all the categories of thinking that pertain to our own personal thought patterns. This can help ensure we have a grasp of the thought genres that are relevant to us before we start to work with them in the described manner.

When we define genres of thinking and apply them to our thoughts as we notice them, we become more familiar with our habits of mind. And as with the other methods mentioned, we foster non-identification with the content of our thoughts.

4. Praise the noticing of thinking

Any moment in which we notice we were lost in thought is a moment of waking up to the here and now. It’s a moment of mindfulness. One simple way we can foster this awareness is to offer ourselves praise or a warm welcome for returning. When we notice we’ve come back to the present moment we can give ourselves a friendly “welcome” or imagine applause and confetti, or simply smile inwardly.

This method of offering ourselves a reward for returning to presence allows us to imprint on our mind that inhabiting a space of embodied awareness is a valuable experience worth repeating.

All four of these techniques are quite simple. However, this doesn’t mean they’re easy. When cultivating mindfulness of thoughts via these methods, and mindfulness as a whole in general, it’s best to adopt an attitude of patient persistence. Also, it’s best to work with one of these methods at a time rather than attempting to work with all of them at once.

Over time, and with many repetitions, these practices allow us to cultivate greater degrees of clarity, joy, and freedom.

Mindfulness of thoughts in daily life

In our busy day to day lives, amidst our familiar tasks and routines, our mandatory errands and obligations, we often operate on autopilot. We’re perpetually caught up in a trance-like state of doing, not noticing what’s happening in our own minds and hearts. We’re unawake at the wheel; driving the car but not in the car.

Meanwhile, thoughts arise and fall away. And instead of seeing them as independent, transient phenomena, we end up being so immersed in them we feel we are them. And so we get pulled to and fro, enslaved to our mind states without ever noticing the shackles we’re wearing.

Mindfulness practice can help us wake up to the here and now and loosen the binds that restrain us. And though meditation is a key component of this practice, it’s not the only one. We also need to exercise our mindfulness muscle in daily life if we want it to grow stronger.

Training ourselves to label thinking as thinking, to notice thought genres and stages of thinking, and to offer ourselves praise when we notice we’re lost in thought can and should be applied both on and off the meditation cushion. In fact, working with these practices during our daily lives is just as essential as working with them when we meditate.

At first, this can be challenging, but starting small can make practising mindfulness in the midst of our lives more manageable. Here are a few simple suggestions:

- Schedule mindfulness pauses. We can choose one small period of time (three to five minutes is good) during the course of our day to pause and practise mindfulness. This might be during a lunch or coffee break, after dinner, before bed, or at any other point that makes sense to us. We don’t have to close our eyes. We can simply tune in to our present moment experience, paying particular attention to the thoughts, perceptions, and sensations that are currently present.

- Practise during transition periods. There are many points of transition, or moments when we’re moving from one activity to the next, that occur during the course of our daily life. Some examples include leaving and entering our home, getting in and out of bed, starting and finishing a meal, and stepping in and out of our car. We can use these brief periods to practise checking in with ourselves and notice what thoughts are present.

- Choose one task to perform mindfully. Another small practice we can adopt is to bring mindfulness to one of our daily tasks. This might be brushing our teething, combing our hair, driving to work, eating lunch, or anything else we do regularly. While performing the chosen task, be aware of any sensations and notice where the mind goes.

These methods of practising mindfulness in daily life can help us be more aware of our thinking, and allow us to grow our capacity for mindfulness more generally.

It’s also useful to remember our cognitive biases can lead us astray and to question our limiting beliefs when we encounter them. It’s important to keep in mind that we don’t have to believe our thoughts.

Final thoughts on thoughts

When we become mindful of our thinking, we can start to recognize the role thoughts play in shaping our reality. And, by developing the capacity to observe them, we can begin to unravel our beliefs and see them for what they are—mental constructs that may or may not align with reality.

With mindfulness, we gain the ability to discern between the thoughts that serve us and those that hinder us. We become able to question the validity of our perceptions and challenge the narratives that hold us back. And in doing so, we can open ourselves up to new possibilities and ways of being in the world.

Ultimately, mindfulness of thinking is about reclaiming agency over our own minds. It’s about recognizing that we’re not our thoughts and that we have the power to choose how we relate to them. By cultivating awareness of our thoughts, we become free to live with greater clarity, presence, and joy.

Ev Nittel is a mindfulness meditation teacher and the founder of An Unabridged Mind, where she helps women cultivate self-love through embodied and benevolent awareness. She writes about quieting the inner critic, building an inner ally, and practising self-compassion in daily life. Learn more and explore her resources at An Unabridged Mind.