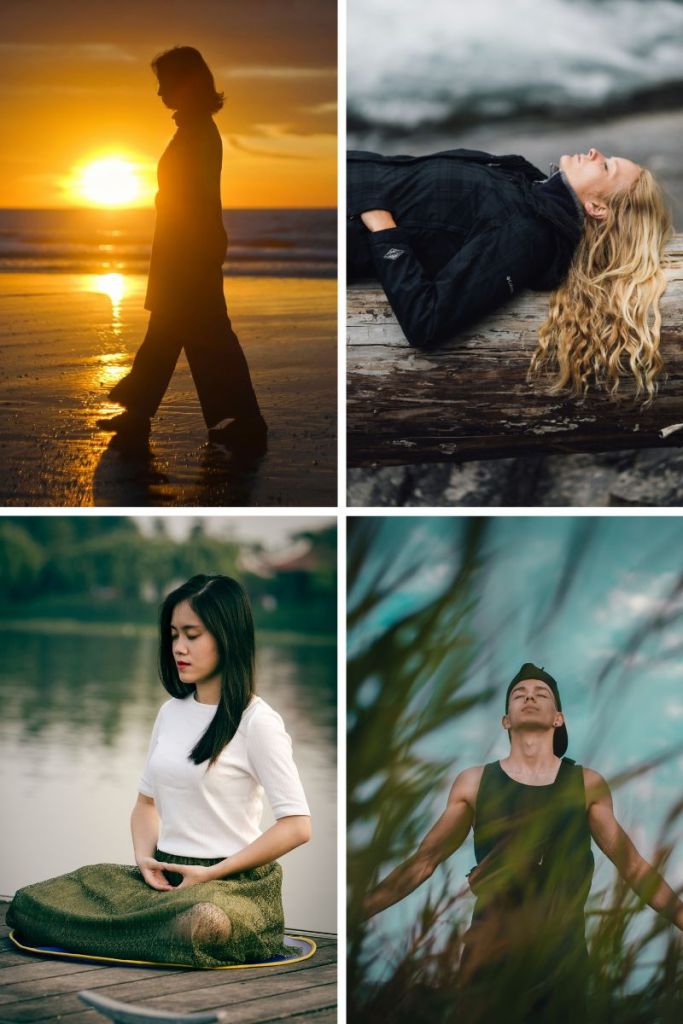

Mindfulness meditation can be practised in any posture that allows you to be relaxed and alert. However, sitting, standing, lying, and walking are the four classic poses mediators tend to employ. For good reason, these postures have been used by Buddhists, yogis, monks, nuns, and other devotees for thousands of years. And, they continue to be effective for the modern practitioner. Whether you want to meditate to improve your health, cultivate calm, sharpen your mental focus, increase awareness, or enhance your spirituality, these four meditation postures can be adopted and applied to your practice.

1. Sitting

If you close your eyes and consider the word meditation, you may envision someone sitting on the ground with their legs crossed and their hands resting on their knees in chin mudra (a hand position in which the tips of the thumb and index finger are touching and the remaining fingers are extended). Certainly, if you plug in the word as a search term in your internet browser and scan the image results, this somewhat romanticized depiction is what you’ll see.

However, in reality there are a number of ways to assume a sitting posture for meditation. You don’t necessarily have to sit on the ground, keep your legs crossed, or hold your hands in a particular position.

When it comes to sitting meditation, what’s important is to find a posture that fosters both wakefulness and ease, and this can mean different things for different people. Ideally, the spine will be erect, the shoulders loose, the jaw and forehead relaxed, and the hands resting comfortably. Beyond these general guidelines, there’s a fair amount of room for variation.

On the ground

Positioning yourself on the floor is a great option. In addition to offering a solid and stable base for your practice, it can foster a sense of being grounded and connected to the earth. For some, this way of meditating can also enhance a feeling of embodiment and presence. Plus, since sitting on the ground has deep roots in the ancient wisdom traditions of the East, practising this way can provide a sense of belonging to a long lineage of practitioners.

To position yourself, you can simply sit cross-legged (a.k.a. sukhasana), with each foot tucked under the opposite thigh. To ensure proper circulation and alignment, it’s important for the hips to be slightly elevated above the knees. You can accomplish this by placing a cushion or folded towel or blanket under your backside.

Alternatively, you may want to adopt one of the following postures:

- Lotus. This position (padmasana) has been practised by yogis for thousands of years and involves sitting with each ankle resting on the opposite thigh. It helps with alignment, provides stability and symmetry, and can reduce muscle tension in the back. However, it requires a fair amount of hip flexibility and for some people (i.e. those with hip, ankle, or knee injuries) this way of sitting offers more risk than reward.

- Half lotus. More accessible to the general population than lotus, this position (ardhapadmasana) is one most meditators can rest in comfortably. It involves sitting with one ankle resting on top of the opposite thigh while the other ankle rests on the floor underneath the opposite thigh. The posture offers most of the same benefits as lotus.

- Burmese. In this position the legs are placed in front of each other on the floor with both the feet and knees resting flat on the ground. The legs are not crossed directly but are placed one in front of the other. As with sukhasana, elevating the hips above the knees facilitates better alignment and circulation. This posture is ideal for those with limited flexibility.

- Seiza or thunderbolt. The traditional posture in zazen meditation, as well as various Japanese martial arts, is known as seiza. This same position is also used by yogis in India where it is referred to as thunderbolt or diamond pose (vajrasana). It is assumed by kneeling with the backside placed directly over the heels and the feet resting under the body. The big toes may touch or overlap. Sometimes a small bench, block, or cushion is used to sit on. The posture offers symmetry and facilitates keeping a straight spine.

In all of these sitting postures, the ideal placement for the hands is one that promotes ease and alertness. They can be lightly placed on the thighs or knees (either palm up or palm down) or rest together on the lap in dhyana mudra. In the latter case, the right hand rests in the left hand with the fingers aligned on top of each other and the tips of the thumbs touching.

On a cushion or bench

Sitting on the ground to meditate may be a more feasible option if you use a cushion or bench. A cushion placed under your backside can enhance the basic cross-legged posture (sukhasana) as well as the Burmese posture. In seiza or thunderbolt, either a cushion or meditation bench can be used.

When used correctly, cushions and benches can help you maintain a straight spine while you meditate. They can also alleviate pressure placed on the knees and ankles. These advantages are likely to make it easier for you to sit for an extended period of time.

Here are some specific tips for using these meditation props:

Meditation cushions

Opt for a meditation cushion (also called a zafu) that elevates your hips above your knees. It should have enough padding to support your weight without feeling too hard or too soft. Firm cushions will provide more stability, but softer cushions offer more contouring.

You should also consider the filling material. Some common varieties of stuffing for meditation cushions include buckwheat hulls, kapok, polyester fibre, cotton batting, wool, and foam.

Most meditation cushions are either round or crescent shaped. Both are good options.

If using a round cushion, it’s important to sit on the front third of the cushion. This will allow your pelvis to tilt slightly forward. Crescent-shaped cushions naturally encourage this positioning.

Remember to keep your knees flat on the ground and your spine straight. A slight tuck of the chin can help ensure proper alignment.

Meditation benches

A meditation bench (also called a seiza bench) should support your weight evenly, allowing you to sit comfortably for an extended period without experiencing strain or discomfort. It’s best to choose one that’s suitable for your height and weight, so if at all possible, test out a few before buying one.

Most benches are made of wood or bamboo and built with a slight downward tilt. Some are designed with inbuilt cushioning, while others have no padding at all.

Some mediation benches are adjustable, allowing you to customize their height or angle to your preferences. Others are portable, made with a foldable design and constructed from lightweight materials that make them ideal for easy transport.

When using a meditation bench, you kneel on the ground and then sit back onto the surface of the bench. Your feet will be tucked underneath it, with the shoelace part of each foot pressed against the floor. Make sure to position your knees hip-width apart to promote stability and balance.

If you desire, you can place cushioning under your knees and/or ankles to further reduce pressure on these joints.

If you decide to use a cushion or bench, it can be a good idea to place a large flat square cushion called a zabuton beneath it. This will further enhance your comfort. You can also use a folded blanket or yoga mat in a similar manner.

In a Chair

For many people, sitting in a chair is a better option than sitting on the floor or on a cushion or bench. This sitting posture can be particularly beneficial for individuals with limited flexibility and those with knee or back issues.

The ideal chair for meditation is one with a straight back, flat seat, and no arm rests. Its height should allow you to rest your feet flat on the floor with your knees at a 90-degree angle. It’s best to avoid overly soft chairs, as they can make it more likely that you’ll slump.

To ensure your spine remains upright, it’s best to sit close to the edge of the chair. If necessary, you can lean against the back of it, but do your best to keep your spine erect. You can use a cushion or rolled towel for lumbar support (this is especially useful if you tend to slouch when you sit). You might also want to place a cushion on the chair to tilt your hips and pelvis forward.

When practising sitting meditation in a chair, be sure to position your feet flat on the ground and hip-width apart as this will lend you a sense of stability and balance. If you’re too short to do this comfortably, you can place a small stool or a couple of yoga bricks under your feet.

Remember to relax your shoulders, unclench your jaw, and let your hands rest lightly in your lap or on your thighs.

2. Lying

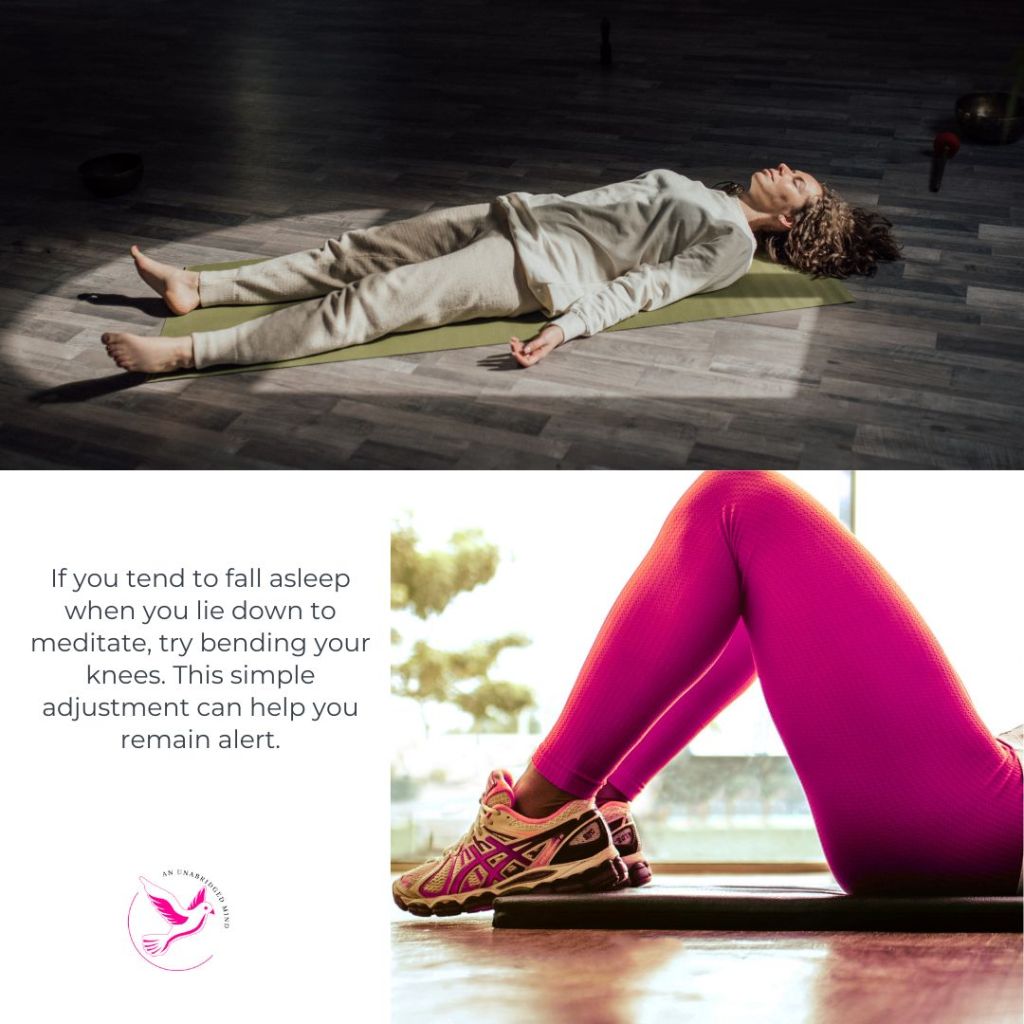

Meditating in a supine position is ideal for anyone with an injury or illness that makes it difficult or impossible to practise while sitting, standing, or walking. It can also be a good option if you’re experiencing a lot of agitation or restlessness.

Though lying down meditation offers most of the same benefits as other traditional postures, it does come with one major drawback: the tendency to fall asleep. Humans are biologically primed to slumber in a supine position, and assuming this pose during your meditation practice can easily cause you to drift off into dreamland.

When practising meditation while lying down, it’s best to position yourself on the ground. A hard surface will help you keep your spine straight and make it less likely for you to doze off. For cushioning, you can use a yoga mat, rug, or folded blanket. Lying in a bed, especially one you regularly use, is less than ideal as it will increase the likelihood you’ll fall asleep.

As with all meditation postures, its best to choose a position that supports both comfort and alertness. When you lie down, this means positioning yourself on your back. To ensure proper alignment, keep your legs hip-width apart and place your hands at your sides with your palms facing up (as you would in savasana).

Ideally, your head will rest directly on the ground. If you must use a pillow, choose one that’s relatively thin. If the pillow is too thick, your alignment will be thrown out of balance.

To help you stay awake in this meditation posture, you can:

- Drink a cold glass of water before you begin

- Set the intention to remain awake

- Bend your knees and place your feet flat on the ground

- Keep your eyes open with a soft gaze directed at a wall or ceiling

- Choose a time of day to meditate when you’re normally energetic

- Practise in a cool, well-lit room

- Focus on a meditation anchor like your breath, body sensations, or ambient sounds

It can also be helpful to use a guided meditation when practising in this posture, as the facilitator’s voice may help you remain alert enough to remain awake.

3. Standing

If you’re tired or drowsy, practising standing meditation is a great option as this posture has an energizing quality to it. It can also be a good fit for someone who’s more accustomed to standing than sitting during their day and for anyone with knee arthritis or another health condition that makes sitting difficult.

To practise in this pose, place your feet either hip- or shoulder-width apart. The legs should be straight with the knees slightly bent. This micro-bend will help prevent you from placing undue strain on your joints and foster a stabilized stance.

As with sitting and lying down meditation, it’s important for the spine to remain erect. You might imagine the crown of your head being pulled up toward the sky and your tail bone being pulled down toward the earth. Keep your shoulders relaxed and let your arms hang naturally. If you prefer, you can keep your right hand cupped in your left hand with the thumbs touching (a.k.a. dhyana mudra) in front of your lower abdomen.

In standing meditation, you may find it’s easiest to maintain a sense of balance if you practise with your eyes slightly open, keeping a soft downward gaze directed at a neutral point on the floor. You can also practise with your eyes closed but you might sway or wobble if you do.

Standing can be used as a primary posture when you meditate or as an occasional supplement to sitting. Though it’s more physically demanding, this type of meditation posture is versatile and powerful, offering increased energy and alertness.

4. Walking

You can adopt mindful walking as both a formal and informal practice. When practising formally, you simply designate a certain amount of time and space to developing your capacity for mindfulness while walking back and forth.

To begin, choose a path of approximately 10 metres (30 feet) in a place where you’re unlikely to be disturbed. This pathway can be either indoors or outdoors.

At the start of the practice, simply stand in place for a moment. You can take a few deep breaths to steady yourself, then bring your attention to the balls of your feet. It’s traditional in walking meditation for the feet to be the primary focal point or anchor. You may find it helpful to be barefoot, but this isn’t essential.

Your hands can rest loosely at your sides or you can keep them clasped either below your navel or behind your back. It’s best in this practice to keep your eyes open with a soft gaze directed at the ground.

As you start to walk, try to notice each movement of each foot. Opt for a pace that’s slow enough for you to observe these micro-movements but not so slow that it becomes difficult to maintain your sense of balance. Try to notice as each foot comes into contact with the ground. Observe the shifting of your weight with each step and the contraction and expansion of the various muscles used.

When your mind starts to wander, gently bring your attention back to your feet.

At the end of the path, pause for a moment, then mindfully turn around. Try to maintain your focus on your feet as you pivot. Pause for another moment after your turn, then walk the path in the opposite direction toward your starting point.

If walking isn’t accessible to you, a comparable practice can be done in a wheelchair or by simply raising your arms up over your head and then down again. In these scenarios the hands rather than the feet become the focal point for the meditation.

The duration for this practice can be as brief or long as you deem suitable. Ten minutes is a good place to start if you’re new to it. Once you’ve established a felt sense of the practice, you can experiment to find the duration that works best for you.

Walking meditation is a beautiful practice in its own right, but it can also nicely complement a sitting practice. If you’re feeling overly tired or anxious, walking may be more beneficial than sitting or lying down. This practice is also often used during meditation retreats and during long practice sessions of several hours or more. As a formal meditation posture, it offers the same opportunities for insight and awareness as other postures.

Conclusion

Meditation is a versatile practice that can be adapted to suit your needs. There’s no one right way to practise, and it’s important to consider your unique preferences and limitations when choosing a posture. By exploring a variety of meditation poses, you’ll learn what works for you and when.

Remember, what’s best for you may vary over time, and it’s wise to remain flexible about how you practise. Whether you sit in stillness, move with intention, or rest in relaxation, each meditation session will provide you with an opportunity to deepen your capacity for presence and peace.

Ev Nittel is a mindfulness meditation teacher and the founder of An Unabridged Mind, where she helps women cultivate self-love through embodied and benevolent awareness. She writes about quieting the inner critic, building an inner ally, and practising self-compassion in daily life. Learn more and explore her resources at An Unabridged Mind.